The Golden Age of Japanese Pencils, 1952-1967

It was the summer of 1952, and the executives of Tombow Pencil were about to revolutionize the Japanese pencil industry—or, possibly, fall flat on their faces. Hachiro Ogawa, the son of founder Harunosuke Ogawa, was Tombow's managing director, and he had just finished a years-long project, at enormous cost, to make the best pencil Japan had ever seen.

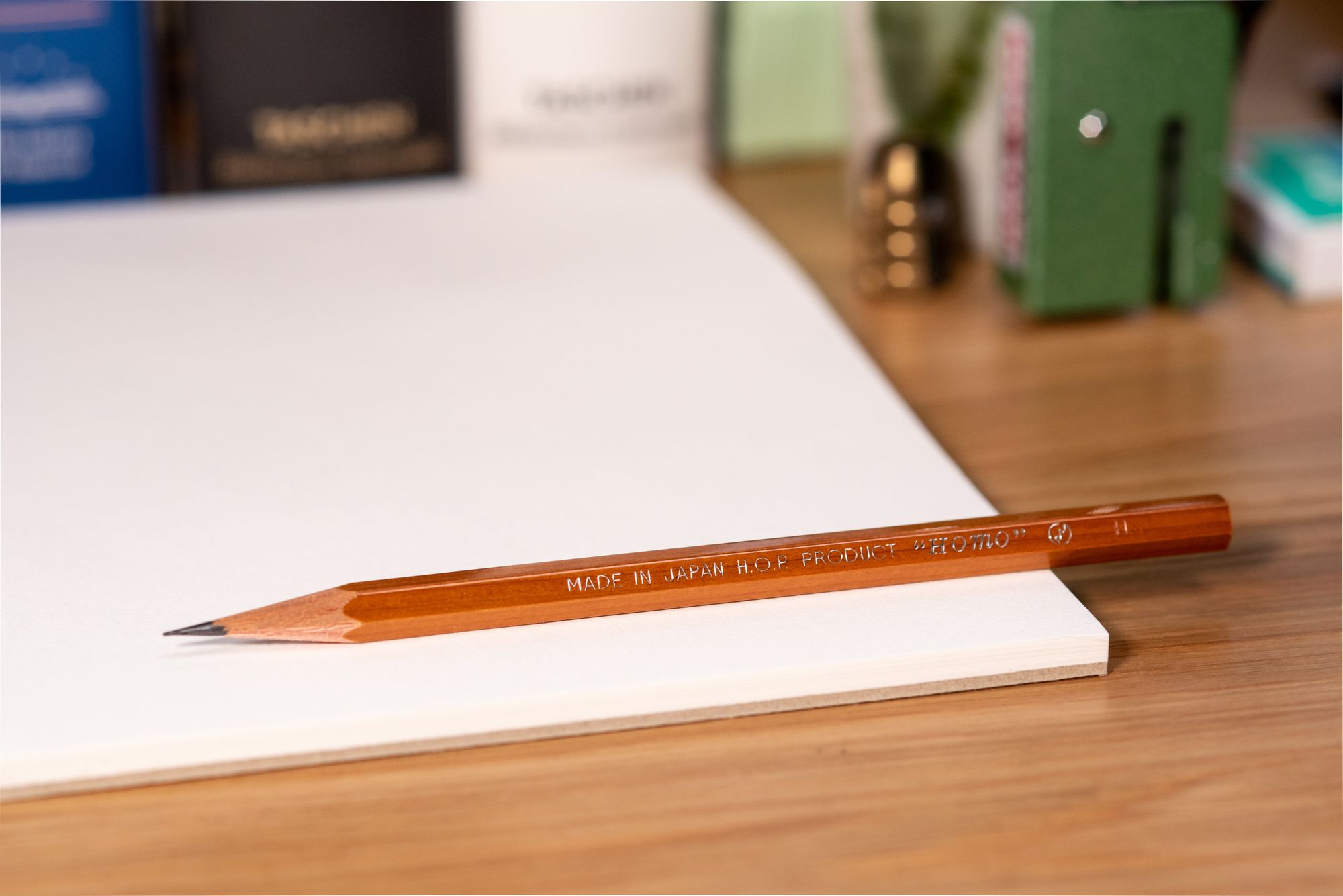

It was called "HOMO," because in comparison with other Japanese pencils of its day, Tombow's new model had a much more homogenous core. Pencil cores are a mixture of graphite and clay (thanks to Nicolas-Jacques Conté's invention of the modern pencil in the late eighteenth century), and the components in early cores were not always evenly mixed. This was particularly true in Japan, where pencils had only been made since the turn of the century and advanced industrial equipment was just starting to become available.

Hachiro's team at Tombow was determined to do whatever it took to produce more consistent cores. They struck up a working relationship with scientists at the University of Tokyo, a visionary move that yielded crucial technical research in 1948. Then, to implement the research findings, Tombow had to import more advanced industrial mills from the United States.

It was a gamble, but it worked, and suddenly Tombow could make much finer particles of graphite and clay than any other Japanese manufacturer. HOMO cores were stronger, smoother, and more consistent than anything else on the domestic market. They came in 17 grades, from 9H to 9B, a wide and finely graduated range that hadn't been possible with Tombow's old process.

They were also incredibly beautiful. Another import that had become available in the wake of World War II was incense cedar, the material of choice for high-quality pencils. Most of the pencil industry's incense cedar comes from California, and Tombow quickly restarted its imports of the aromatic red wood. HOMO's design takes full advantage of the material upgrade, with a subtle transparent lacquer that highlights the cedar's color and grain.

For Hachiro Ogawa and his father Harunosuke, the completion of the HOMO project was the culmination of a dream, and it was undoubtedly a pioneering moment in Japanese industry. But as the company prepared to introduce HOMO at the grand Tokyo Kaikan meeting hall, the skeptics must have been hard to ignore. In the early 1950s, a Japanese pencil cost five or ten yen (about 25-50 cents in 2022 dollars.) Tombow's technical leap forward had produced a model far superior to those inexpensive pencils, but they would also be pioneers in price. HOMO would cost 30 yen (about $1.50 today) for a single pencil, with boxes of twelve priced at 360 yen (about $19 today.)

Japanese consumers weren't used to spending that kind of money on a pencil. But if Hachiro, Harunosuke, and their colleagues were nervous, their fears were surely resolved at the first-ever Tombow New Product Presentation. Tokyo Kaikan was the esteemed meeting place of foreign dignitaries, corporate titans, even heads of state—and now it was absolutely bustling with stationery wholesalers, curious people from other companies, and the press. Tombow took orders for 720,000 HOMO pencils on launch day alone.

Tombow's surprising success with Japan's first premium pencil, along with the ambition and competitive spirit of midcentury manufacturers, led to the most intense period of development the global pencil industry has ever seen.

We call it the Golden Age of Japanese Pencils.

The Golden Age began and ended with two Tombow launches: Hachiro's pioneering HOMO launch in 1952 and the MONO 100 launch in 1967, fifteen years later. During this period, Tombow and its crosstown rival Mitsubishi Pencil created many of the greatest pencils of all time, including the two best-regarded models offered today.

Prologue: The Great Tokyo Pencil Rivalry

Although HOMO was the first Japanese pencil with a modern core, Tombow wasn't the first pencil manufacturer in Japan. That was Jinroku Masaki's pencil factory, which delivered three grades of writing pencils to the Japanese Ministry of Communication in 1901. Masaki had been introduced to the pencil at the Paris Expo of 1878, and he was one of a few Japanese industrialists to learn about the new technology in depth.

Masaki established a small pencil manufacturing firm in 1887, and just four years later, he had improved his products enough to land a government contract. To commemmorate the three grades of his "ministry pencil," Masaki had the idea to register a three-diamond trademark, along with the "Mitsubishi" name, which means 'three diamonds.' (It may surprise you to learn that this was ten years before the much better-known Mitsubishi Group of heavy industry companies registered its name and identical mark. Mitsubishi Pencil has no connection to the numerous other Mitsubishi companies in Japan; it is and has always been a manufacturer of writing and drawing supplies.)

Tombow's predecessor, Harunosuke Ogawa Pencil, was a small Tokyo retailer established in 1913. The 28-year-old Ogawa and his wife Towa were energetic and resourceful, and they built their business in tandem with their growing family. They soon decided to try their hand at manufacturing, and the first H.O.P. brand pencil, the Mason, was released a year later.

The two companies grew and innovated in parallel. As the 100 Year History of Tombow Pencil puts it, Mitsubishi and Tombow were "good rivals," who pushed one another to new heights, collaborated in joint ventures overseas, and worked together to develop new industry standards. (As we'll see, they also copied each other shamelessly.)

In the early years, Tombow led the way in structuring the pencil market, creating new brands and grades intended for different types of users. Before World War II, Tombow introduced several forward-looking models. H.O.P. Drawing Pencils (1928) came in 14 grades and were Japan's very first complete line of artist pencils. And Tombow's groundbreaking Model 8800 (1936), with a formula devised to rival the leads made by German manufacturer Stabilo, influenced other Japanese pencils for decades after its introduction.

Tombow's technical advantage was the product of its early investment in a modern, centralized factory, where all the trades involved in pencil manufacturing would coexist under one roof. The new Toshima Factory opened in 1927, during one of the worst economic crashes in Japanese history. Nevertheless, the new facility allowed Tombow to outpace Mitsubishi and the other, smaller competitors in product development for almost a quarter century.

It was only after Mitsubishi opened its Koyasu Factory (still operational today, but now called Yokohama Office) in 1940 that the older company began to catch up to its rival. After the war, Mitsubishi and Tombow set to work releasing a series of nearly identical everyday pencils: the green-and-gold Mitsubishi 9800 with "matured micro graphite lead" in 1946, the green-and-gold Tombow 8900 with "micro crystallite" lead in 1948, and the (yes) green-and-gold Mitsubishi 9000, "Made By Elaborate Process." All three of these pencils, made on the cusp of the Golden Age, are still manufactured and sold today.

Green and gold, by the way, is the color scheme of Castell 9000 pencils, which were among the best in the world at the time. The Japanese companies had honed their process, but they hadn't developed the confidence and brand identity to step out of the shadow of European manufacturers. Fueled by their early success and a quickly changing world, the rivals were about to change that.

The Industry Gets Really, Really Organized

As they improved their products and competed in the global market, Japanese manufacturers were keen to build a reputation for quality and reliability. To that end, the government worked with a wide variety of industries to enforce quality standards for different types of products. The system, which persists to this day (but no longer includes pencils), is called the Japanese Industrial Standards, or JIS.

The JIS Daily Goods Subcommittee researched, deliberated, and consulted with experts to develop the pencil standards, which were officially adopted in 1951. Just two years later, an astonishing 90% of pencils made in Japan had met the standards and completed certification. These pencils displayed the JIS mark 〄, which appeared on quality Japanese pencils until the industry was eventually deregulated in 1998.

It may sound excessive to create a national standard for pencils, but these everyday products were very important to Japan's economic strategy. In the highly regulated postwar days, the government prioritized light industry, which produces consumer goods like pencils. That policy decision gave the pencil companies a head start in securing resources and capital. Even more importantly, as the decade went on, Japanese consumers simply had more money to spend. From 1950 to 1960, average wages in Japan rose by 250%.

Perhaps it isn't surprising, in retrospect, that Tombow's ultra-high-end HOMO pencil was an immediate success. And the rest of the industry wasn't far behind, because the science behind Tombow's new production process wasn't proprietary. As the product of a public-private collaboration with the University of Tokyo, the 1948 core research was available for anyone to read—and everyone did.

So, when HOMO created the premium pencil segment in Japan, the 109 other pencil manufacturers weren't caught flat-footed. As the Golden Age began, they raced to develop even more consistent cores, with finer-ground particles and thicker lacquer than the competition. Inspired by the case included with HOMO, Golden Age pencils often featured thick plastic storage cases, with transparent windows to display the increasingly refined and complex writing tools inside.

They proudly stamped their pencils in gold and silver foil, engraving them with English superlatives like "Supreme Quality" and "Master Writing." They made limited editions wrapped with illustrations and painted in special colors. And if one manufacturer advertised 100 million particles, another wouldn't be far behind with a 200-million-particle pencil.

Mitsubishi Goes Back to the Drawing Board

Yoji Suhara, director of engineering at Mitsubishi (and next in line for the chairmanship), wanted to know what the West thought of his company's pencils, so in 1953, he went on a fact-finding mission to Europe and the United States. He brought boxes of Mitsubishi 9000 pencils, their highest-quality model at the time, and asked local users what they thought about Japanese pencils.

Suhara was crestfallen to learn that his products had a poor reputation in their most important export markets. Consumers couldn't tell the difference between Mitsubishi's relatively advanced pencils and those from other Japanese producers who had emphasized production speed over quality control. The fact that the whole industry used similar color schemes and four-digit model numbers was confusing, particularly since they were, in many cases, exactly the same color schemes and model numbers as European manufacturers' well-known brands.

Suhara returned to Tokyo with a bitter taste in his mouth and a mission: to make a high-end pencil not just to top Tombow, but to show the world that Germany no longer had a monopoly on quality pencils.

Back in Japan, Mitsubishi's engineers were already poring over the University of Tokyo pencil core research. Dramatic changes to the mixing, molding, and firing processes were all on the agenda, along with upgraded raw materials. Suhara and his colleagues tested 17 types of clay, finally settling on a variety sourced in Germany. To make the raw clay particles finer, Mitsubishi invented a new method of removing impurities; in recognition of this achievement, they earned a 30 million yen ($1.5 million today) subsidy from the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

In addition to these technical improvements, Suhara wanted to make sure no one would confuse the new pencil with any other product in the world. It had to have a contemporary, well-considered, and unquestionably original design. In perhaps the best strategic decision in Mitsubishi's long history, the company hired Yoshio Akioka, who had recently designed the iconic Asakaze "Blue Train."

In an unconventional move, Mitsubishi gave Akioka extensive creative control over the project from the beginning; the esteemed industrial designer even suggested the price—50 yen ($2.50 today), the same price the European manufacturers were charging at the time.

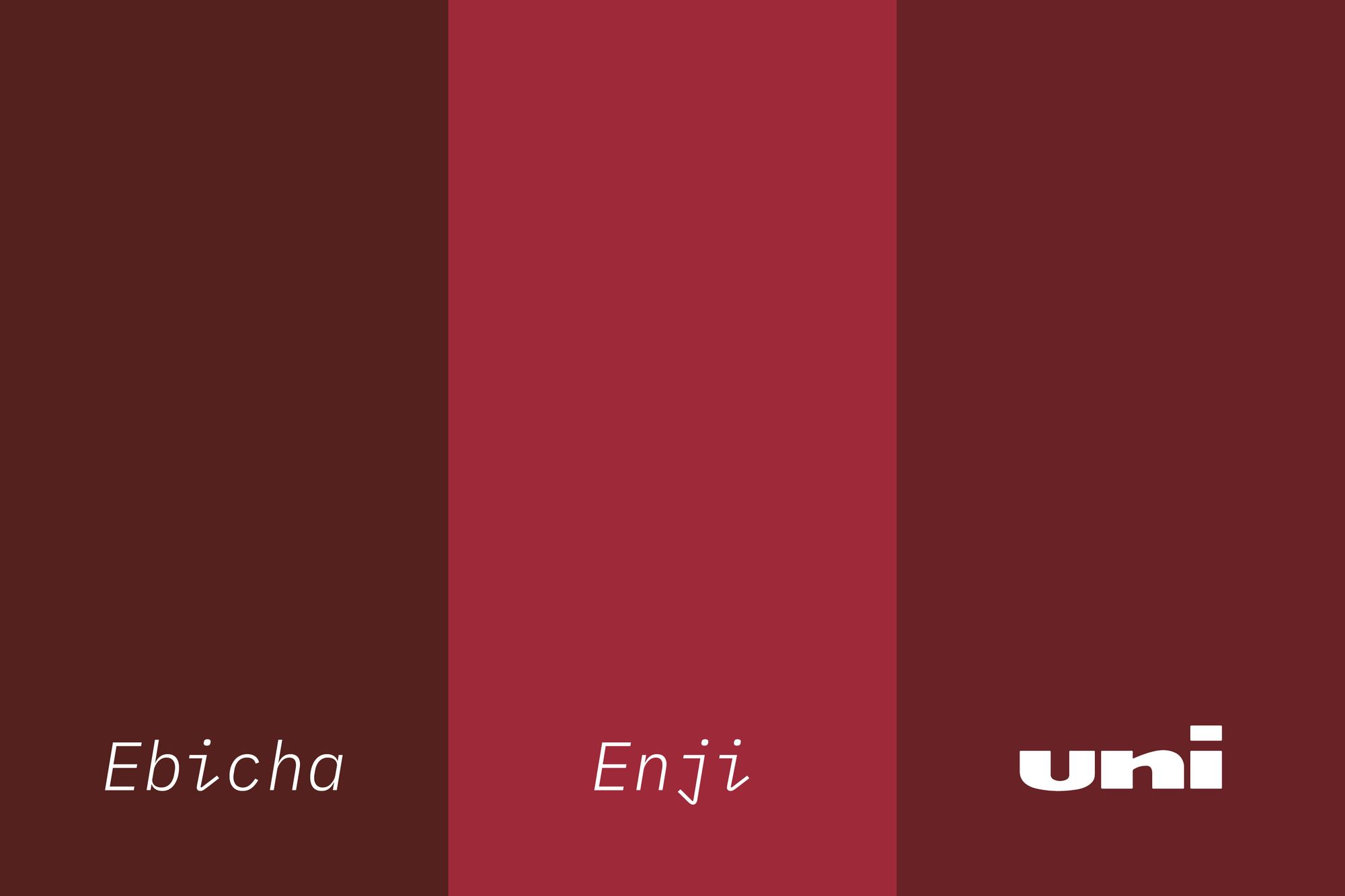

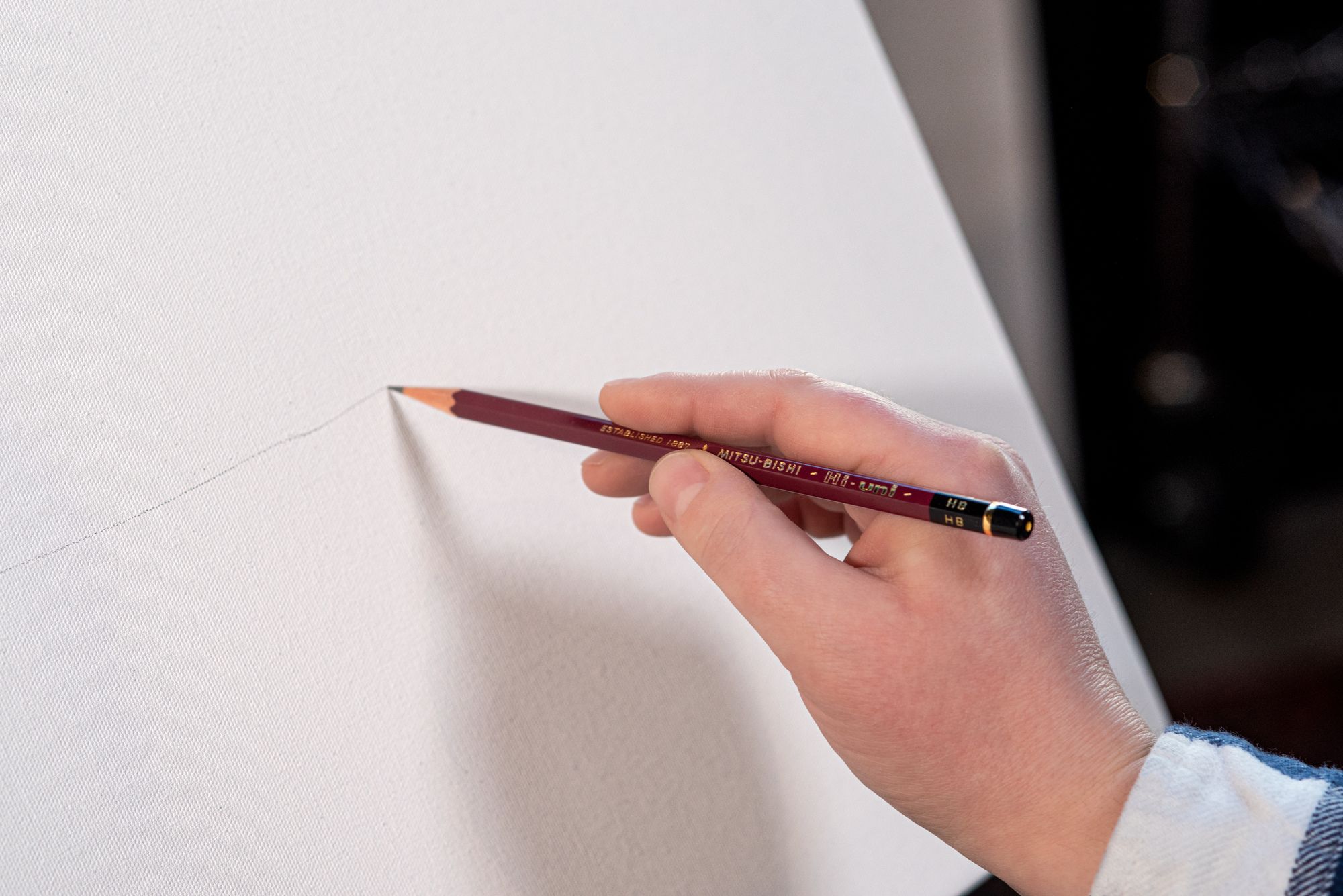

One of Akioka's most important contributions was the color, an iconic maroon that's now synonymous with Mitsubishi pencils. The world's best brands all had a signature color, like Faber-Castell's deep green and Staedtler's bright blue. For Mitsubishi, Akioka chose a shade that felt distinctively Japanese, halfway between the traditional colors enji (wine red) and ebicha (maroon).

To make sure the color would be unique to Mitsubishi, Akioka ordered 160 pencils from manufacturers all over the world. No one had painted a pencil quite this shade of red before.

Akioka named the new pencil, too—"Uni," short for the English word 'unique,' but also French for 'smooth.' Imagining the architects of the future drafting homes with Uni pencils, Akioka designed the timeless, rounded "uni" logotype, with wide, sturdy typography. As he put it, he wanted the Uni brand to be "a house that warmly wraps people up," instantly familiar and comfortable.

Today, most of Mitsubishi's global customers identify the company with Akioka's Uni brand, which Mitsubishi quickly began to use on a variety of other office supplies and stationery. In the United States, everyone knows Uni-ball pens, but not many people know that they're made by a 135-year-old company called Mitsubishi. That's a testament to the success of Akioka's work in the mid-fifties.

It was clear soon after Uni's 1958 launch that the pencil was a success. The maroon, gold, and black pencil was an instant status symbol and a genuine object of desire for students. From a technical perspective, Uni remains one of the best pencils ever made, surpassing European and domestic rivals with its ultra-smooth, impressively dark graphite.

Akioka's futuristic design influenced the rest of the industry, and Uni pencils have been a fixture in Japanese schools and offices ever since. The company continues to manufacture them, almost exactly as they were 64 years ago.

Eight Billion Particles Per Cubic Millimeter

At Tombow, Hachiro Ogawa had become the company's president following Harunosuke's death in 1957. Hachiro and his younger brother Kohei worked to broaden Tombow's product line, launching their first mechanical pencils in 1957, markers and ballpoint pens in 1958, and an electric sharpener in 1962. But even as Tombow and Mitsubishi expanded their offerings into new kinds of writing tools, the pencil rivalry was not quite over.

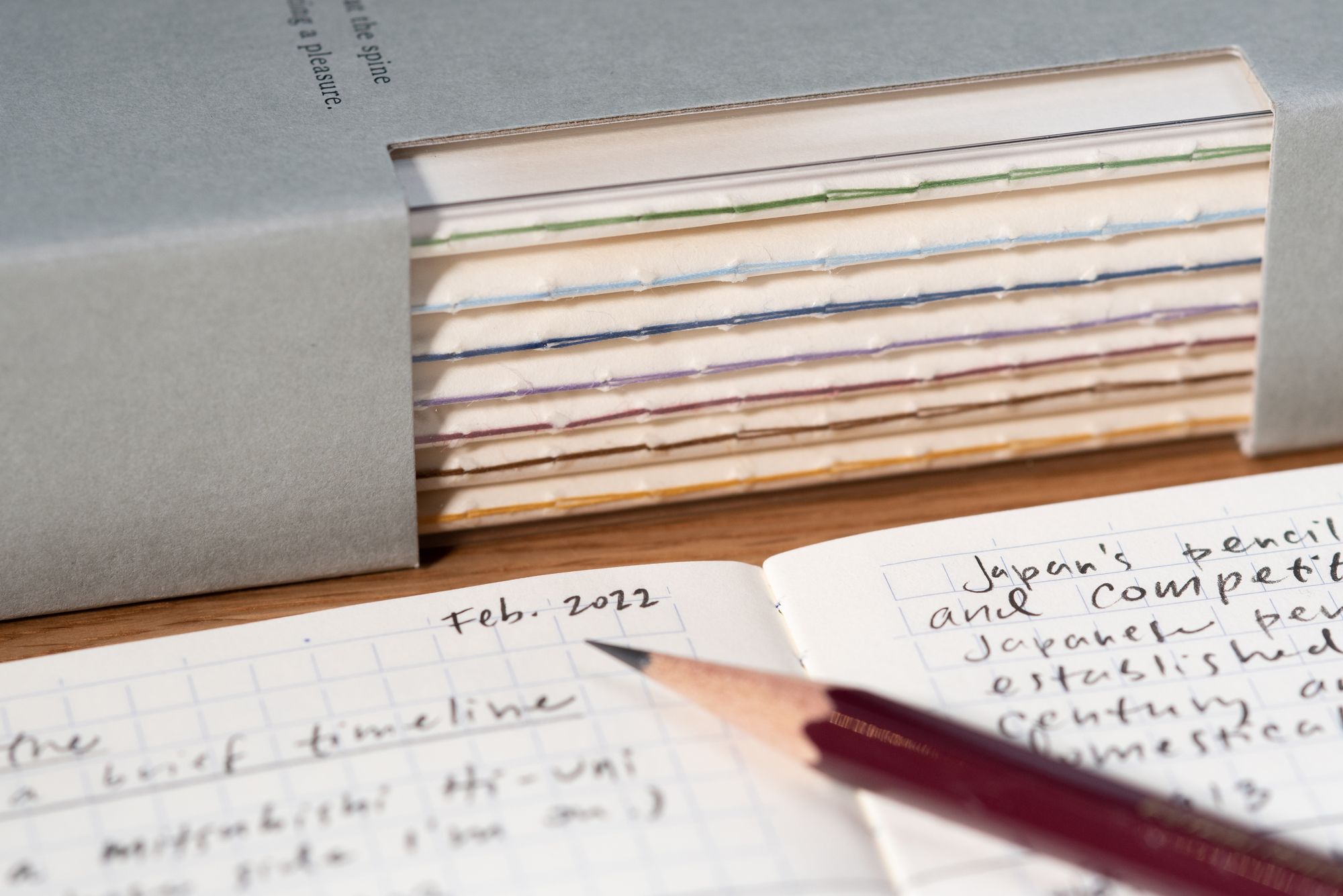

In 1963, Tombow replaced its decade-old HOMO pencils with the newly renamed and completely redesigned MONO brand. The new name (created upon Tombow's belated discovery of the English meaning of "homo") was suggested by Tombow technical consultant Akamatsu Noriyasu, who had been a primary author of the University of Tokyo pencil core research. MONO comes from the Greek monos, which Tombow translates as "unique and unrivaled."

With a new, glossier design in black, gold, and white, plus advertisements touting "8 billion particles per cubic millimeter" and a prestigious pricetag of 60 yen (20% higher than Uni), Tombow MONO was a direct response to Mitsubishi's groundbreaking design. The dynamic of the rivalry had changed again after a half-century of competition. Now Mitsubishi had the initiative, and Tombow had to match its rival's advances.

The New Chairmen

In April 1963, four months before the release of MONO, tragedy struck Tombow's Ogawa family when Hachiro died suddenly. Kohei, the younger brother, was appointed Hachiro's successor only six years after Hachiro replaced Harunosuke. Towa Ogawa, Harunosuke's wife and collaborator, known for her early embrace of the mass media, would live only one year longer than her oldest son. She died in 1964 and was one of very few women to be awarded Japan's Order of the Sacred Treasure that same year.

Understandably, the launch of MONO was a moment of mixed emotions at Tombow. Hachiro's latest leap forward was a success, and the MONO brand became just as important to Tombow as the Uni brand is to Mitsubishi. But the innovative older brother wasn't there to see the outsized results of his short six years at the helm.

In large part because of Hachiro's modernization efforts in the forties and fifties, MONO pencils are still used by artists and writers, and MONO brand stationery in virtually every category is a familiar sight in shops around the world. Hachiro's vision in creating HOMO laid the foundation for Tombow's next 50 years.

Mitsubishi was also undergoing a generational shift. Chairman Saburo Suhara retired in 1960, and his son Yoji, champion of the Uni project, became the company's new leader. After MONO's release in 1963, Suhara and Mitsubishi understood they would have to respond. Pencil production and demand had continued to grow, as had the number of pencil manufacturers in Japan. In 1960, there were more than 200 of them.

But creating a pencil even more luxurious than Uni would not necessarily have a big impact on the company's performance—a pencil that refined would certainly be a niche item, not sent in schoolchildrens' backpacks like Uni. Further, the writing (if you'll forgive the bad joke) was on the wall for pencils as a universally important, in-demand item.

Pens and mechanical pencils had supplanted wooden pencils, which no longer seemed so convenient in comparison with a ballpoint. Mitsubishi, in fact, had already started making pens in 1959 and mechanical pencils in 1961. Following Pentel's commercialization of fiber-tipped pens in 1963, Mitsubishi introduced its own porous point pens in 1965.

So, although Mitsubishi and Tombow didn't know in advance that the Japanese pencil industry would reach its peak in 1966, both companies clearly saw it coming, and they had already prepared themselves for a future beyond pencils. One wonders why both companies continued to expend research and development resources on high-end pencils in the late 1960s, but they did—and on a personal note, this sometimes inexplicable tendency of Japanese manufacturers to perfect what doesn't need to be perfected is a major reason why we're so passionate about our Japanese imports.

Faced with a coming drop in demand and with successful, high-quality products already on the market, many Western companies would have started cutting costs, not investing in further improvements. Indeed, the truly innovative days of German and American pencil manufacturing were already over. But thanks to the competitive, perfectionist leaders and designers at Mitsubishi and Tombow, the late 1960s yielded two more historic pencils.

The Last Premium Pencils

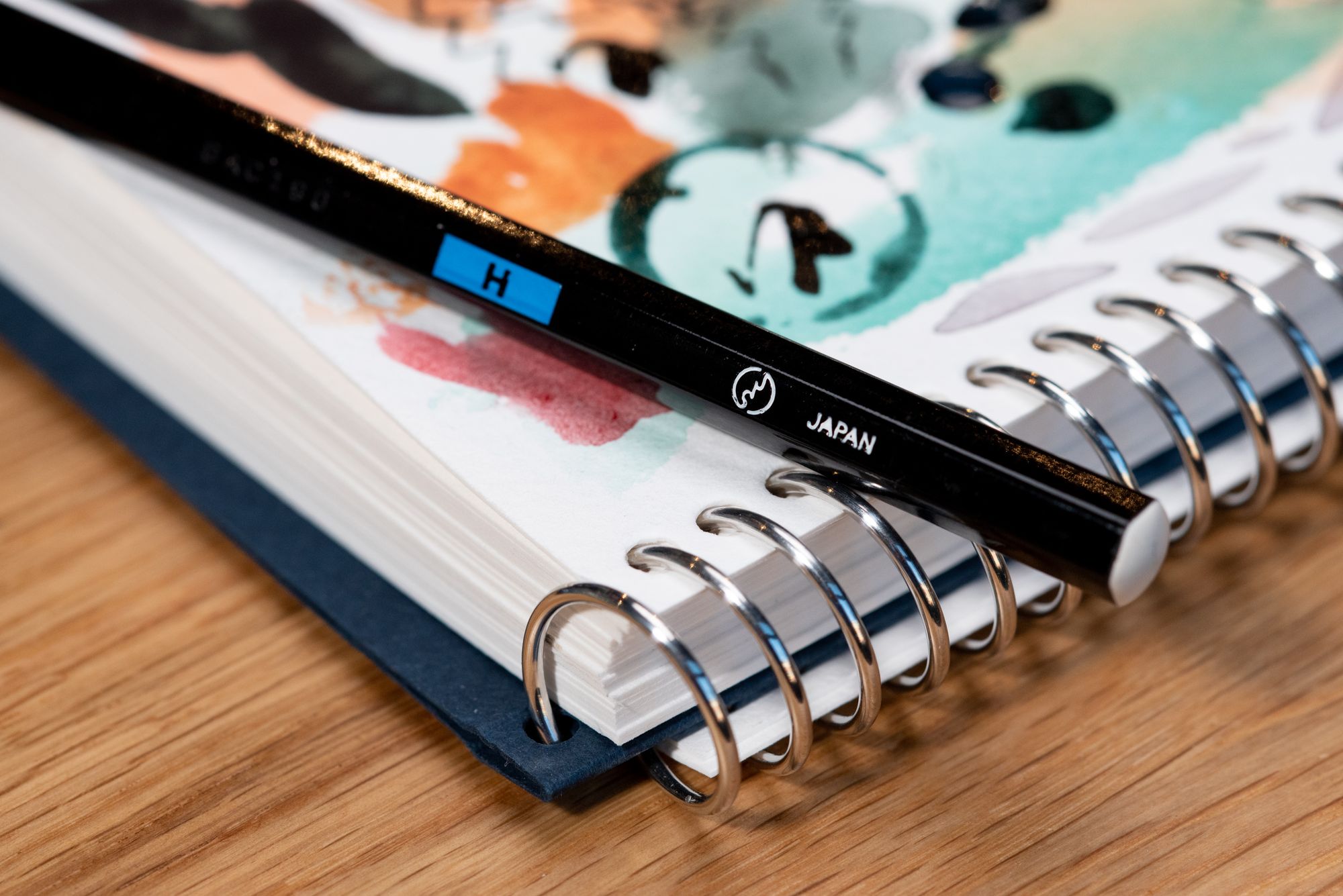

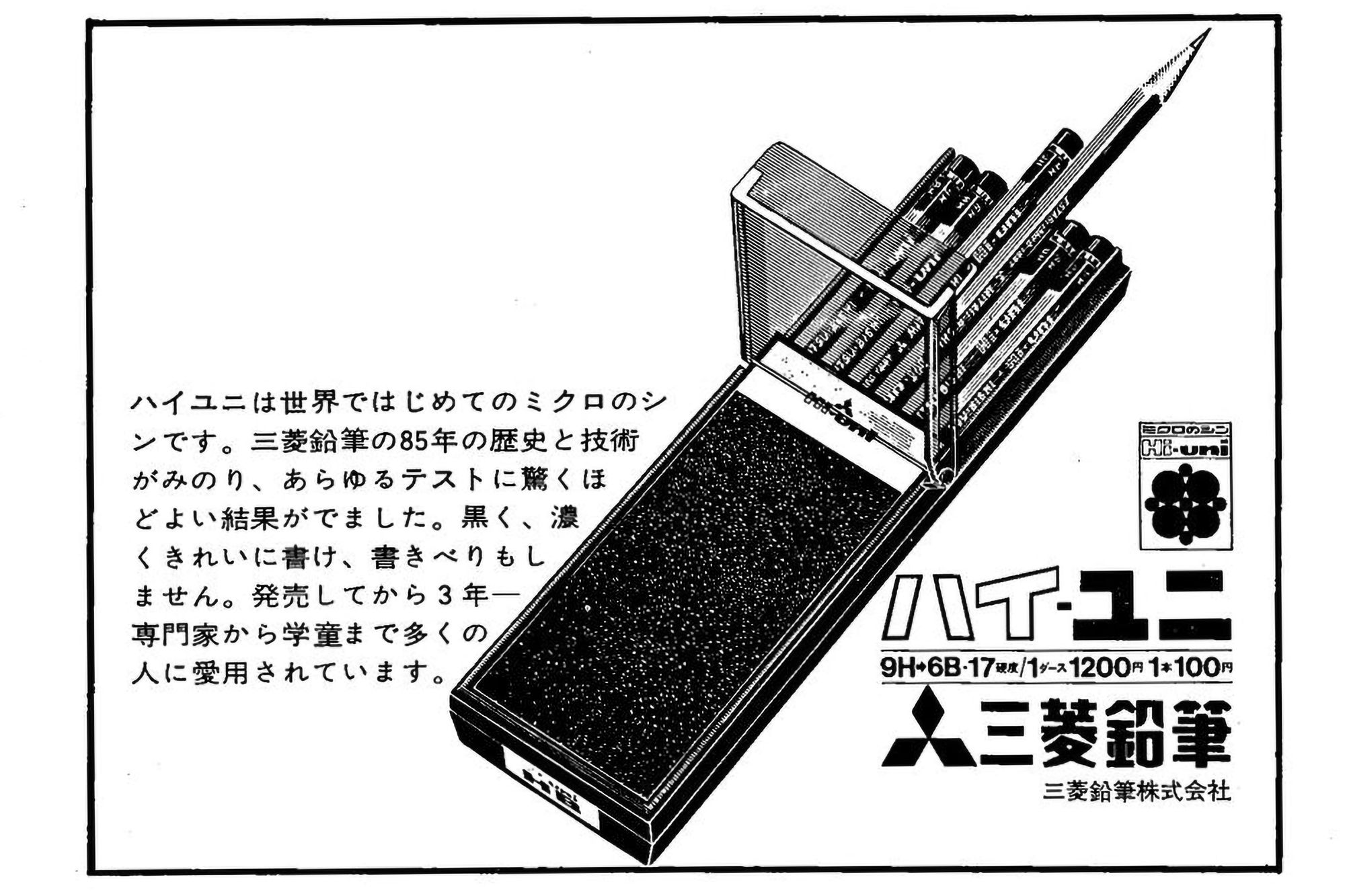

In 1966, precisely at the peak of the Japanese pencil industry, Yoji Suhara's Mitsubishi introduced Hi-Uni, an upgraded version of Yoshio Akioka's eight-year-old Uni. We all know that sequels (especially those released after the commercial peak of the franchise) tend to be disappointing, but Hi-Uni is the rare exception. Rather than overcomplicating or underappreciating Akioka's design, Mitsubishi improved on it in every way without diminishing its modern style.

Hi-Uni came in a wider range of grades, resolving a key shortcoming of the original model. (The current Hi-Uni is offered in an amazing 22 grades, with 10B added to the lineup just recently.) The core boasted Mitsubishi's latest technical innovation, which went beyond simply minimizing particle size to actually maximizing particle density by combining particles of different sizes in a precise ratio. And no expense was spared in sourcing and screening the raw materials for this very precious pencil.

The result (and here, I'll reveal a strongly held personal belief) is the greatest pencil ever made, in any country, before or since. For Mitsubishi's designers, the ideal pencil would have "6B blackness with 9H hardness," able to make very dark marks while also wearing down slowly and offering pinpoint precision. Hi-Uni's core, with its innovative mixture of particle sizes, comes pretty close to this unachievable ideal. Better yet, despite its excellent point retention, Hi-Uni lead is also the industry leader in smoothness.

Hi-Uni was an authoritative and complete response to Tombow MONO, and it launched with the same legendary status it retains for pencil lovers today. At a princely price of 100 yen each in 1966 (that's almost $4 in today's dollars!), Hi-Uni represented the almost excessive pursuit of perfection in simple things. It spoke to the desire for a rich and comforting everyday life. And it expressed the powerful optimism of 1960s Japan.

Tombow wasn't far behind with its own aspirational pencil, and MONO 100, the last premium pencil launched by either manufacturer to this day, appeared in stores in 1967. It was perhaps a sign of an emerging détente that MONO 100 debuted at exactly the same retail price as Hi-Uni: 100 yen each.

Taking a page from Mitsubishi's book, Tombow hired a well-known industrial designer, Takashi Kono, to update the MONO design. Kono had been involved in high-profile projects like the Olympics and the World's Fair and was one of the most accomplished adesigners in midcentury Japan. His design for MONO 100 is a genuine classic, with a cooler, slicker, and simpler look than the soft-edged, stately Mitsubishi Hi-Uni. It's particularly recognizable for its white stripe, jauntily painted in a vertical arc over the endcap.

From an industrial design standpoint, Tombow stuck to its strategy of milling finer and finer particles. The MONO 100 advertisements claimed "10 billion particles per cubic millimeter," up from 8 billion for the original MONO. This design concept makes MONO 100 different from Hi-Uni in a few important ways. MONO 100 is more precise and longer-wearing than the same grade of Hi-Uni, but somewhat less smooth and dark.

Those differences make the Hi-Uni / MONO 100 debate a sort of personality test. Do you prefer creamy, super-dark graphite, and are you okay with sharpening more frequently? Would you enjoy using a pencil with a design that connotes luxury, elegance, and composure? Then Hi-Uni is the pencil for you. But if, instead, you prefer sharper, more defined marks, with less smudging, less sharpening, and a futuristic look, then MONO 100 might be a better choice.

The Golden Age Never Ended

Isn't it strange that this historical essay includes purchase recommendations? That's kind of the beauty of our weird little industry. Most of the pencils discussed in this article are still manufactured and sold, even though there would never be another pencil launch to top Hi-Uni and MONO 100. Mitsubishi and Tombow each expanded and modernized their businesses, and today both are heritage brands with large, diversified product lines.

For those of us who love pencils—the design and typography, the nostalgia, the irreplaceable sound of smooth graphite on paper—the end of this story is bittersweet. Pencil manufacturing is not really an industry of its own; very few companies today specialize in wood pencils alone, and certainly no large companies do. Pencils have vanished from offices and are used mainly by artists and students. Since the 1970s, many historic European and American brands have actually decreased in quality. Frankly, we have to accept that Hi-Uni and MONO 100 will probably not be improved upon.

But is that such a bad thing? Maybe Mitsubishi never fired back with a "Hi-Hi-Uni" because pencil manufacturing had reached a natural point of diminishing returns, where any further increase in quality would be virtually imperceptible. Today's manufacturers are not racing to improve the pocket knife, for example, because the technology is mature and the major flaws have been sorted out by past generations. Many of the most revered brands, like France's Opinel, have made the same knives for decades, and they cut just as well as they always have.

In this pencil merchant's opinion, there's simply no need for a pencil more perfect than the best of Japan's Golden Age. We can admire the heady moment and the strong personalities who created these pencils, and we can be forgiven for daydreaming about the even-more-perfect pencil, the one that would make our handwriting beautiful and our drawings perfectly proportional.

But when I sit down to sharpen my pencil (usually a Hi-Uni HB or Mitsubishi 9852 "Master Writing" B), my primary feeling is gratitude. The designers and engineers who created these tools didn't know they would be made for 70 years, but they treated their seemingly small task with intense seriousness of purpose, and that passion produced outstanding tools that have still not been surpassed. Today, in 2022, I frequently speak with artists who tell me how much these pencils inspire them and enable their best work.

So I'm not regretful about the end of the Golden Age of Pencils, because in the ways that matter most, it never ended. Mitsubishi, in particular, has loyally maintained its midcentury product line, continuing to manufacture its pencils in Japan and even adding a minor new model now and then. (There's an antiviral-coated Mitsubishi in light blue, new for 2022.) Artists and writers still debate the merits of Hi-Uni and MONO 100.

And I can't speak for everyone who works here, but personally, I'm excited every time I ship a fresh, unsharpened dozen to a new customer. For them, the Golden Age is just getting started.

References

Feenstra, Robert C., Robert Inklaar and Marcel P. Timmer, "The Next Generation of the Penn World Table," American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150-3182, available for download at http://www.ggdc.net/pwt

Japan Pencil Industry Cooperative Association, "The history of pencils and the Japanese pencil industry," 2001. http://www.pencil.or.jp/company/rekishi/rekishi.html

NTT Comware Co., "Long seller: Mitsubishi Uni pencils," Comzine, volume 23, issue 5 (2005). https://www.nttcom.co.jp/comzine/no023/long_seller/

Tombow Pencil Co., Ltd., 100 Year History of Tombow Pencil, 2013. Free Japanese ebook available here.